|

Copper River Record February 2017 By Robin Mayo With the returning sun, there is more motivation to get outdoors on skiis or snowshoes, and explore some of our trails in winter. In fact, winter is the preferred time to travel across wetlands easily without risking damage to the fragile and essential ecosystems. The Tonsina River Trail heads south from mile 12.3 of the Edgerton Highway, and goes about 1.3 miles in a gentle downhill, first to the bluff, then west along the bluff to a gorgeous picnic spot overlooking the river. WISE often uses this location as an outdoor classroom where we can learn surrounded by panoramic views, birdsong, and the spicy scent of sage. There is a nice pullout on the south side of the road where you can park, and a small kiosk at the trailhead. The first half of the trail tends to be wet in the early part of the summer, and of course with our boots we dig the trench deeper and wider, compounding the problem. I like to wait to use this trail until a good dry spell, or towards the end of summer. Or why not explore it in winter and avoid the mud altogether? Locals ski this trail fairly often, so there is a packed base to support cross-country skiis or snowshoes. Like so many of our Copper Basin trails, the land status is a little complicated. The trail itself is on a 17(b) easement. Test time: who remembers this unique Alaskan land designation from my article several weeks ago on land status? Gold stars all around! In a nutshell, 17(b) Easements are special corridors which were created to allow access across lands that were conveyed to Native Corporations by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA.) When I was researching land status for this trail on BLM-Alaska’s Spatial Data Management System, I noticed that the Ahtna region is the only area of the state for which the easement data is complete. Way to go land managers! The easement for the Tonsina River Trail is only 25 feet wide, so please stay on the trail to avoid trespassing on surrounding lands. This trail is a great one for wildflowers, and we often come across wood frogs. Kids always want to hold critters they find, but may be unaware that frogs have a fragile and very important slimy skin covering that can be badly damaged by handling. It is best to observe them as they hop about, then let them go on their way unharmed. I always try to imagine how I’d feel if a giant frog picked ME up… Happy hiking everyone, and be sure to get out and enjoy the “warm” weather! Copper River Stewardship Program 2013 students enjoy the view at the end of the Tonsina River Trail. Kate Morse Copper River Watershed Project Photo.

0 Comments

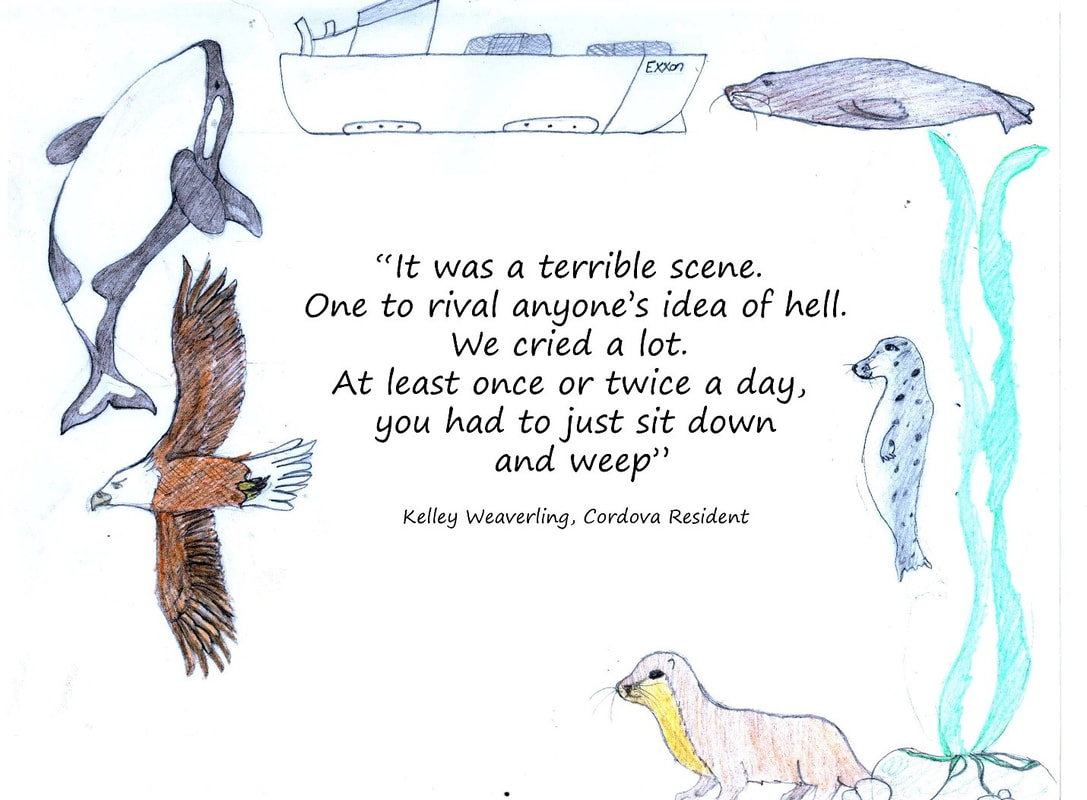

Copper River Record December 2016 By Robin Mayo It’s a picture perfect day as we motor across Prince William Sound on the MV Aurora. The sun is sparkling on pristine water, gulls wheel overhead, and in the distance fishing boats cluster. Some are already pulling their nets, and through our binoculars we see the wriggling masses of glistening salmon rise up then spill onto the decks. On the bow of the ferry, travelers are enjoying the warm sunshine and passing scenery, sharing sightings of whales, otters, and sea lions. They lean over the rails eagerly, craning for a glimpse of Dahl’s porpoises cavorting at the waterline. But in the ship’s lobby, the mood is more somber. A small group of high school students is gathered around a map of Prince William Sound, reliving the night over 25 years ago when the Exxon Valdez ran aground on Bligh Reef. We are transported to a cold night in March when a combination of events sent the tanker out of the shipping lanes, bleeding crude oil into the water. There is no easy answer to the question of “Why?” It is easy to blame the captain of the ship, but hearing the entire story, we learn that he was just one factor in a whole system that failed that night. Once the stage is set, the students are given first-person narratives from Exxon Valdez oil spill responders from the book “The Spill” by Sharon Bushell and Stan Jones. They are asked to put themselves in the shoes of the men and women who were there, then create a piece of artwork or writing to symbolize the experience. Individually or in small groups, they find quiet places on the busy ship to absorb the poignant stories. With the beautiful scenery as a backdrop, they read the pieces quietly to one another. Several hours later, we gather again by the map, with pastel drawings and poems in hand. One by one, the students introduce the narrators, summarize their stories, and share projects. Using their particular talents with words and pictures, the students expressed sadness at the lives and beauty lost, outrage at the injustices, pain at the futile waste. The crew was asleep. Content to place their fate, and the fate of their cargo In the hands of another. Their minds were at rest As they dreamt of the meaningless things That would never again occupy their thoughts. Little did they know that the meandering of their minds Would be rent apart by the sound of unforgiving, crushing rock Wreaking havoc on the hull. Little did they know this sound would forever haunt them, That their dreams would be filled with the sound That resulted in the release of liquid death. The sound that condemned thousands of souls to heartbreak and misery. The sound that destroyed an entire ecosystem. And yet they slept on. Oblivious to this wretched fate. Dreaming as Mother Nature held her breath. Nicole Friendshuh Artwork by Alexis Hutchinson

By Bruce James, WISE Executive Director

The Copper River is a very dynamic watershed and is the primary reason many people visit or live in Southcentral Alaska. Understanding the forces that control this ecosystem is a daunting challenge and someday soon the younger generation will be the decision-makers. In an effort to help this generation become enlightened stewards, the Copper River Watershed Project, Prince William Sound Science Center and Wrangell Institute for Science and Environment (WISE) have developed a program to provide the opportunity for a select group of high school students to learn about the Copper River in way that few ever experience. The youth learn about salmon, forests, glaciers, wildlife, climate change, and the entire watershed ecosystem. The highlight of the program is a multi-day raft trip down the Copper River itself, providing participants with a chance to get to know the river from a first-hand, personal perspective. Perhaps a parent of a previous participant summed up the program’s value best by saying, “The benefits from exchanges of ideas and friendship between quality people in the program, coupled with the educational aspect, make this a winner for all involved. I hope this opportunity will be available for many years to come.” Much of the support for this unique opportunity has come from the generosity of communities along the river. However, funding for this year’s event is short and the scope of the program may have to be reduced. You can help, with donations of time or money. Further information and ways to sponsor a Copper River Ambassador are available at www.wise-edu.org or www.pwssc.org, or by calling 907-822-3282. Please help us continue this exceptional educational experience by making a donation today. In early August, ten high school students from the Copper River Basin rafted from Chitina to the Million Dollar Bridge on the Copper River, on a trip organized by Wrangell Institute for Science and the Environment (WISE).

The two days preceding the trip were packed with presentations from various local experts on watershed subjects: fish hatchery, local history, fish species and management, Native subsistence, conservation of the watershed, geology, pipeline safety and spill response, boating safety. Instructors for the raft trip included Janelle Eklund of WISE, Glenn Hart of WRST, and Carla Schierholt as photographer. The trip was guided by Alaska River Expeditions. Student participants prepared essays on their river experiences, excerpted below. The essays and more students experiences and photos will be shared at community presentations. From the Essays Mark Henspeter, from “The Copper River: Changing and Connecting”: “Originating at the terminus of the Copper Glacier near the northern border of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, the Copper River is a reasonably small river, carrying only its own load of silty water from the glacier due north, before turning south towards its ultimate destination at the delta near Cordova. “From this point on, however, as the river picks up the burden of many well known tributaries such as the Gulkana, Tazlina, and Klutina rivers, in addition to numerous others, the Copper River becomes consistently wider, more voluminous, and ever siltier. By the time it reaches the flats along the coast, nearly 300 miles from its origin, the Copper River delta stretches nearly 50 miles side to side, and according to the Copper River Knowledge System, dumps an incredible amount of nearly 750,000 cubic feet of sediment into the Pacific Ocean every day! “Although it sounds staggeringly huge, this figure became very believable to me once we were actually on the water, as the sound of the silt and sediments actually became an audible hiss against the bottom of the rafts. “In all reality, the Copper River is not simply one river – it is dozens of rivers, hundreds of streams, and countless mountain drainages, all tied together to form one coursing channel to the ocean. Clearwater streams abounding with fish wind their way into the Copper, as well as alpine glaciers, depositing their fresh loads of silt into the murky ice-cold waters of the river. With each additional tributary into the Copper, the character of the river changes yet again – in temperature, color, capacity, or contents – with each leaving their own unique mark upon the river.” Mary Marshall, from “Lake Atna”: “Lake Ahtna covered approximately 2,000 square miles of lake bottom floor about 30,000 to 10,000 years ago. It covered what is now known as the Copper Basin including Glennallen, Kenny Lake, Tazlina, Gulkana, Copper Center, Gakona and more. In fact, some scientists say it was larger than Delaware. It also was in the center of many incredible icefields. At the last ice age, it created a huge dam for Lake Ahtna to rest in. When the glaciers receded, it made room for what is now known as the Copper River to flow through. Those glaciers are now called Allen, Miles and Childs glaciers which are located near the “Million Dollar” bridge.” John Giraldo, from “Glacier Power”: “The topography of the Copper River was further changed when Alaska entered the mini ice age, which lasted from 1650 to the beginning of the 1900's. This mini ice age caused what glaciers remained to advance, changing the landscape of the Basin, particularly in the lower Copper River region. One of the most notable feature caused by this ice age that we were able to observe on our raft trip was the Bremner sand dunes. While we were not able to see the top half of these dunes due to high winds which made a huge cloud of silt, we were able to see the bottom half the next day when the wind had subsided. They stretched on for miles. It was amazing to see the amount of debris that these glaciers were capable of moving. “Now, 9,000 years after the lake drained, the glaciers have continued receding, making the channel between the two glaciers, which at one time was a formidable rapid, into a four mile wide lake called Miles Lake. Miles Glacier is receding at a rapid pace, while Childs seems to be able to maintain its size fairly well. However, like all other glaciers, these glaciers calve frequently, making enormous waves as they crash into the water. “Both glaciers stand approximately 300 feet tall, making the splash of the falling ice even more dramatic. I was able to observe both glaciers calve, but Childs glacier was definitely a better show. “While both glaciers calve off enormous chunks of ice (some are city block sized!) Miles Glacier was over a mile away from where we camped, so most of the energy of the wave was depleted by the time it hit the shore. However, we were only a river’s width away from the Child’s Glacier, so when huge chunks of ice fell off it was spectacular. While we didn’t actually observe it happen, sometimes the waves. . . are so huge that they beach fish, making it easy for bears to eat the salmon.” On the experience as a whole: “It is a privilege to be able to experience Alaska in this way.” Wade Jones, from “Traversing the Copper River”: “On the back side of Woods Canyon, the currents separate in the three to five different currents. At this point on the trip this was the first point I was able to row. This day the guide was telling me which current to go to at what time I needed to get over there. But by the third day I was able to see which currents were faster and I could anticipate when I needed to move the raft. “Day three was slow and was a nice leisurely drift down river. Day four was by far the most interesting. Going through Baird Canyon, the rapids are not that fast or hard to maneuver through. “The next part of the river called Abercrombie Rapids was probably the best part of the river. In the canyon the water formed one current that was fast but still slower than Woods Canyon. Then through the rapids the water is forced through a narrow alley way and drops elevation very quickly and creates some very tall swells. This section of the river was fun for us because we were with experienced guides and traveling downriver.” On the experience as a whole: “The experience of learning and being able to raft the river was one of the best things that I have done with my life so far.” Kimberly Woods, from “Human Uses of the Copper River Past and Present”: “On March 20, 1885, Lt. Allen and his crew of two, Sergeant Cady Robertson and Private Fred Picket left Nuchek or Hinchinbrook Island, which is now the trading station of the Alaska Commercial Company, for the mouth of the Copper River. They had two boats and guns; they packed lightly and off they went up river. The Allen Expedition’s main purpose was to map the Copper River, find resources, and meet natives. “Along the way, Lt. Allen met natives and traded with them for food, supplies, and information. Many Ahtna villages treated them as guests. Allen and his crew hunted with the natives. Allen’s maps were amazingly accurate and guided future miners and trappers through the Copper Basin. “Lt. Allen observed how the natives caught fish using dip nets and fish traps. As years have gone by, dip nets and fish traps are still used, and starting in the early 1900’s, fish wheels appeared in the Copper River.” Mary Anne Carlson, from “Shaping the Landscape”: “The first day traveling on the river I was astonished at how strong the currents were. As we left the land near the Chitna bridge, we had not gone far before we met up with the Chitina River. It flowed directly along side the Copper River which created bigger ripples in the water. The raft I was in instantly adapted to the two different currents and we floated at a faster pace towards our destination. Throughout the five days on the river I experienced many currents, volume changes, and different depths of water. “The volume of the water appeared to be smaller toward the beginning of the trip. However as we floated day after day I realized how much the volume of the water increased further along the river. One reason for this volume change is the many other rivers that flow into the Copper River, making it bigger in volume size. At one point on our trip the river was approximately six miles apart from bank to bank. “The depth of the water changed throughout the trip as well. There are many things that affect the depths of the river. For example glacier bound lakes, snow and glacier melts, rainfall, and water discharge will all increase the depth of the water. However, there are also many things that restrict the water elevation on parts of the rivers: the large sand dunes and eroded banks. These have an instant affect on the depth of the Raging Copper River.” On the experience as a whole: “The scenery, watching the wildlife interact with the river, and the quiet time of listening that I had every day was unforgettable and life-changing.” Michael Helkenn, on “The Wilderness of the Copper River Watershed”: “Huge mountains, some snow-capped, all covered in thick vegetation, flanked the banks of the Copper River as the raft expedition passed slowly through this unique wilderness. Bears patrolled the shores, searching for a tasty salmon meal. Bald eagles flew overhead, also preying on the salmon swimming up the river to spawn. . . “The largest and most noticeable aspect of the trip were the mountains. Alaska is covered in large mountains and boasts the tallest peak in North America. Everybody here in the Copper River basin are familiar with the Wrangell and Chugach mountains, as those two ranges surround us in our basin. However, those two ranges are many miles apart. “On the river, less than ten miles from Chitina, we were able to see the full magnificence of Alaska's mountains, as the river literally passed right through them. Steep peaks climbed to heights of over 8000 feet on both sides of the river. These mountains, and everything else for that matter, was covered in thick, dense alder forests. Floating through this Alaskan jungle, I felt like I was in the middle of a tropical rain forest.” On the experience as a whole: “Every place in Alaska is different from all the others.” Naomi Grace Carlson, from “Glacier Winds of the Copper River”: “Our guides on our trip to Cordova would always have us wake up early to get out on the river. This allowed our group to get off the river before most of the winds would hit us. The winds would really start to pick up right around noon time. It was a lot harder to row when you face the fierce winds with the resulting stinging sand and silt. Lucky for our group we only had to experience that one time through our five day trip. But trust me; you do not want to be stranded on the river with those Katabatic winds. “The nice thing about the wind was it was something you really could plan ahead for. Since you knew the Katabatic winds were bound to come, you knew to make sure you had extra clothes to put on and to get off the river early. “Throughout the day there was a complete weather and wind change on the Copper River. The hanging glaciers all through the Copper River affect the climate tremendously. “The mornings had a nice cool breeze but as the day went along the winds became stronger and stronger, changing the current, the scenery, weather, and not to mention clothing. As the sun went down every night the wind seemed to enjoy bedding down for the evening as well. The reason for this was because the cooler cold front glacier winds did not have the heat of the sun to create the turbulence. “ On the experience as a whole: “I got to know and share this wonderful experience with many friends and had plenty of laughs along the way.” Sami Knutson, from “Million Dollar Bridge”: “. . .there were workers who made the bridge and worked through the hurricane winds and glaciers closing in on them. The first piling the workers made along with the rest of them were hollow. They were dug so deep into the Copper River that sometimes when the workers came up, oxygen bubbles would get into their blood streams sometimes causing them to die. “Through long grueling months of work all of the four pilings were finished. The work on the “bridge” had to be done. Through all this time of building the Childs glacier was moving closer and closer to the bridge. After one span had been done the glacier crashed into it and caused the span to fall. This made it so that they had to rebuild the whole section again. To be able to reach the other piling one had to cross the catwalk, sometimes in winds as strong as hurricanes. After one crossing a man swore that he would never cross it again. Then, after four years of grueling work and unlivable conditions, the bridge was completed making way for copper from the Kennecott mines.” Alex Van Wyhe, from “Learning From the River”: “Over the course of the five days that I spent on the Copper River, I learned about many things--ranging from the history of the area to the nitrogen fixers that allow plants to grow along river banks. Every day we saw evidence of people having been on or along the banks of the river. Whether they were there dip netting days before or building a railroad nearly one hundred years ago, we could tell that they’d been there. “One piece of information that I found most interesting explained how all of the sediment came to be in the Copper River. About 70,000 years ago Lake Atna (now spelled Ahtna) was formed when glaciers descended upon the Copper River Basin, absolutely blocking off the drainage of the Copper River. This glaciation occurred during the Wisconsinan Ice Age. Lake Atna was around for some 60,000, years and during this time all of the sediment from the glaciers that were blocking drainage was able to settle to the lake bottom. This sediment deposit is what brought all of the sand found in and around the Copper River. When this huge sediment load is coupled with the winds that howl along the river, it’s easy to see why people are so happy to take a shower after floating the Copper. “Another thing I thought was interesting was how you can imagine what the river was doing at different points in time just by looking at the bluffs along the river. When you look at all the layers that make up those bluffs, it forces you to wonder what was going on in the past that made the bluffs look like that. “At certain points there is sand on top of gravel on top of sand on top of gravel…. While floating past one such bluff, our guide, Robin Irving, shared with me how those layers came to be. Approximately 400 years ago a sort of “mini ice age” occurred. During this period of time the glaciers stopped the flow of the Copper River in the winter, letting the sediment load deposit, then during the summer, the glaciers would open up again allowing the water to flow. “That explains why the layers alternate between sand and rocks. The sand represents the time that the water wasn’t moving because the sediment had time to settle out, and the rock represents the time when the water was moving because the force of the river would have deposited those large pieces while it carried the sand elsewhere.” On the experience as a whole: “I would take this trip again in a heartbeat.” On August first ten high school students from the Copper River Basin were singing “Rowin’ Down the River” as they completed a five day rafting trip from Chitina to the Million Dollar Bridge and Cordova. Wrangell Institute for Science and Environment made this program possible through a grant from the National Park Foundation, American Legion donation, Wrangell St. Elias National Park and Preserve (WRST) in-kind donations, Alaska River Expeditions discounted rates, and a small stipend from each of the students.

In March students from the Copper River Basin wrote an essay on “The importance of the Copper River as a natural resource, its influence as a watershed, and how it affects the surrounding ecosystem” to apply for this program. The program was limited to ten students. Fourteen applied and a panel of four judges chose the winning essays from a list of criteria. Judges were Bruce Heaton from the American Legion, Linda Flint from Copper Valley Telephone, Mark Somerville from Alaska Dept. of Fish Game and WISE board member, and Dave Wellman, WISE vice president. The panel of judges received the essays after names had been excluded. Winning applicants were: Mary Carlson, Naomi Carlson, John Giraldo, Michael Helkenn, Mark Henspeter, Wade Jones, Samantha Knutson, Mary Marshall, Alex VanWhye, and Kimberly Woods. Instructors for the raft trip included Janelle Eklund, WISE president, Glenn Hart, WRST Education Specialist and Volunteer Coordinator, and Carla Schierholt who also was the official photographer. WISE contracted with Alaska River Expeditions to guide the raft trip. Students said they were inspired and impressed by the magnitude and diversity of the river, along with the geologic forces, wildlife, plants, the sheer beauty, and the infamous winds. Before the river trip students spent two days getting their ‘feet wet’, so to speak, by various presentations from experts with local agencies and organizations. This part of the program included a tour of the Gulkana Hatchery at Paxson; acquiring information on fish species and importance of the watershed from Mark Somerville at Alaska Department of Fish and Game; a lesson on GIS/GPS by Josh Scott of WRST; a guided tour by Fred Williams of the Copper Valley Historical Society through the George I. Ashby Museum in Copper Center; a visit to the Ahtna Cultural Heritage site to learn about subsistence from Dorothy Shinn, Donald Johns, and Jack Sabon; a talk from Copper Country Alliance members Ruth McHenry and Cliff Eames about their organization and current focus on the pipeline oil spill contingency plan; an overview of the geology of the watershed by Suzanne McCarthy, director and geology teacher at Prince William Sound Community College; and river safety by Trooper Simeon. At the end of the river trip, in Cordova, Tori Baker from the Sea Grant Marine Advisory Program, gave students first hand knowledge about the Copper River Delta area and the coastal fisheries; students visited the Copper River Watershed Project office where Kristin Smith and Brenden Reilly gave an overview of their organization and projects, focusing on sustainable economic development. Students kept a positive and fun attitude throughout the trip despite being ‘silt blasted’ at the Bremner sand dunes in the high winds that funnel through that area. Copper River silt was imbedded in every pore and orifice of the face, not to mention clothes and gear. It was so thick visibility wiped out any view of the mountains or nearby terrain. But as one student said, ‘it’s all part of the experience’. Observations and notes were taken by each of the students to be compiled into essays and shared with the public and sponsors. Each student was given a topic to write about. A WISE Watershed Leadership Program Essay Series will be published in the Copper River Record so stay tuned for informative accounts from these students. Community presentations from the students will be in September or October. Announcements will be made as to specific dates and times. WISE would like to thank all of the above sponsors and presenters for their contributions, along with drivers, Ramona Henspeter, Bob Jones and Heidi Peters; Suanne Hart for the water bottle clips; and Kate Alexander for the delicious ice cream after the river trip. These contributions gave students the opportunity to gain knowledge that will stay with them for a life time. |

Who We AreWISEfriends are several writers connected with Wrangell Institute for Science and Environment, a nonprofit organization located in Alaska's Copper River Valley. Most of these articles originally appeared in our local newspaper, the Copper River Record. Archives

August 2021

Categories

All

|

|

WISE is a

501(c)3 nonprofit organization |

Contact Us |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed